Student Spotlight: Kat Cognata Partners with Harlem Community Garden

Growing Access:

An ESS Partnership between Pace and a NYC Community

The Electric Ladybug Garden, Harlem, New York City

By E. Melanie DuPuis, PhD

Urban gardens began springing up in cities in the 1980s and are continuing to grow today. Many of these gardens are run by neighborhood boards. However, these boards are continually dealing with the problem of space: how do you make the garden accessible to more people when there is only so much room for so many garden plots and for other uses of these neighborhood spaces? This Pace internship story is about a partnership between Pace Environmental Studies and Science (ESS) and the Electric Ladybug Garden in Harlem. The board wanted to expand the garden in ways that made it accessible to more members of the local community. They asked us to answer the question: how do you grow garden access?

How did you find each other and start working together?

Kat (Pace Environmental Science Student): As an undergraduate Environmental Science major at Pace University, I was looking for research opportunities as well as internships last spring. During that time, Dr. DuPuis told me that the coordinators at the Electric Ladybug Garden were looking for a summer intern. I met with the board and it seemed to be a perfect match. I was able to conduct research at the same site that I would be interning!

Paul Whelen (Electric Ladybug Garden Board): I actually got the idea from the greenhouse manager and science teacher at my son’s public school – PS 333. I told her about the new community garden I was involved in and was admiring the many things in her greenhouse/classroom such as seedlings, hydroponics, renewable energy experiments and composting. She mentioned that the Pace University Environmental Studies and Science Department might be worth approaching about exploring some of these things and might even have students that were looking to work outside the classroom. I knew we had room to grow and was open to any ideas for our space and our community.

Melanie (ESS Faculty Advisor): Paul Whelan contacted me to ask if the ESS Department was interested in “adopting” their garden. In particular, they wanted to expand access to the garden beyond the people who had access to garden beds. They didn’t have enough space to give plots to everyone in the community, but they wanted the whole neighborhood to benefit from the garden. They thought it would be great if a student intern could help them with this issue.

How did you go about establishing the partnership?

Kat: As soon as I was introduced to the board, I was also introduced to various community members. Within only a week’s time, I was working with many of the community members to construct the garden models I would be researching. Throughout my time at the Electric Ladybug Garden, I became acquainted with the majority of the community members at the garden through events and routine garden visits.

Melanie: Paul, his wife Madeline and I discussed several ideas for expanding garden access. But it was only when Kat came to me wanting to work on an urban garden project that it all came together.

How did you decide what specific topic(s) to work on together?

Paul: I have served on the board since the creation of the garden three years ago and Madeline is head of our gardening committee. We had a very fruitful discussion with Professor DuPuis and one of the most exciting and popular ideas was to use the large empty vertical space to expand our community grow beds and supply more free food to the community and hopefully increase engagement. This was later discussed and approved by the board.

Kat: As an intern for the garden, the board was eager for me to introduce new ideas to the garden. Since I was able to use the site for conducting research, I wanted to introduce new models of gardens and see which was most efficient. Ideas were thrown around and then we settled on testing out three different zero space garden models, whose raw materials were paid for by the Electric Ladybug Garden’s grants. The garden members were extremely enthusiastic about the vertical garden models that were introduced to the garden.

Briefly describe the environmental problem you were grappling with and how you went about designing a project to deal with this problem.

Kat: Gardening in New York City isn’t a norm for most communities, as there isn’t much green space in this concrete jungle. Community gardens do exist making it possible to grow fresh food, however they are usually fairly small and squished between the skyscrapers making it impossible for the entire community to have grow space. My garden models were designed to take up zero square footage and make the most out of all the space available in the garden to grow crops. By adding vertical garden models to the walls of the garden, we were able to greatly expand the number of “gardeners.”

Melanie: Maybe being able to snip a few herbs isn’t the same as having your own plot of tomatoes, but if you think of it in terms of the number of days a year a community member can use the garden, this is a significant expansion in use. It also makes the garden much more inclusive by being accessible to community members on a daily basis. As a result, more members of the community can feel a sense of belonging to the garden.

Give us a feel for the kind of work you are doing on this project in terms of collecting and analyzing data.

Kat: This project tested various zero-space garden models to see if they could meet the criteria laid out for me by garden members. The main criterion was access: could we make the garden accessible to more people? Of course, that meant we had to grow food, so I quantified the crop yield for each model. But the models also had to be affordable, easy to use and maintain, and hopefully have a positive effect on the community’s views of the garden. This data I tended to collect in a more qualitative way, through interacting with people in the garden and participating in garden events and workdays. In other words, I collected this more qualitative data simply by spending lots of time in the garden with lots of people.

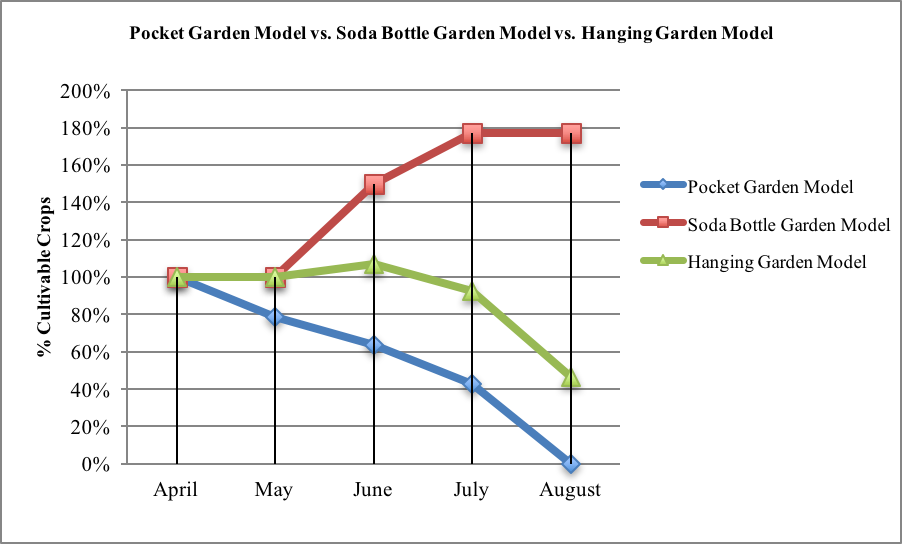

The three models met our preliminary criteria of affordability and ease of use. Those were the ones I tested: (1) a vertical “pocket garden,” (2) hanging pots on the fence and (3) the soda bottle garden. The pocket garden, a commercial product we bought on line, failed to produce any useful food. The hanging baskets grew strawberries and the community – especially the kids – appreciated coming to the garden to eat free strawberries. But that model only worked in spring. The one model that gave community members constant access to garden produce was the soda bottle model. I planted mostly herbs in the bottles and community members were able to come to the garden and clip fresh herbs for their use all summer and most of the fall.

Describe a bit of what a typical week of your internship looked like.

Kat: A typical week usually consists of harvesting, watering, and tending to the crops as needed. On weekends, there are usually events held by members of the garden. There are also workshops on certain days set up by the board. I’m actually going to be hosting my own workshop regarding my most successful vertical garden model, a DIY vertical garden model constructed of recycled bottles. During my workshop, I’ll be showing the community members how to construct a plastic bottle garden either to add to the one already in the garden, or even a small-scale version to bring back to their apartments.

How did it all work out?

Paul: Extremely well! We have greatly appreciated and enjoyed the support from both Professor DuPuis and Kat. Kat has given us far more than just this wall experiment and has been a consistent volunteer, contributing many hours and working hard to improve the garden. We consider her vertical garden a successful experiment and are having another workday to increase the size of it on September 30. Kat is scheduled to help lead this workshop for our community. Our conclusions from Kat’s vertical wall project are that they are popular with the members of the garden, they contain free food so they increase our outreach and goodwill, they look nice and the soda bottles are the most successful of the three types tried so we plan to install more of those.

How has the hands-on connection with a community organization enhanced your learning?

Kat: Many people have different techniques and tricks to gardening I would have never even been aware of if I hadn’t been involved in such an organization. It also has taught me to deal with possible community-based issues in an administrative way.

Working in a community garden, there are many different people of different backgrounds, nationalities, etc. and all of these different people tend to acquire different problems and concerns. With the knowledge I’ve gathered as an ESS major, I was able to design a project that met the desire of a community to have access to local food, even in “zero space” places.

E. Melanie DuPuis, PhD

Professor and Chair, Environmental Studies and Science, Pace University

Recent Posts

Presenting at the Annual Society of Fellows Meeting

Congratulations to Environmental Science student Hannah Engelmeyer ’25 who won awards for their paper and their presentation at the Annual Meeting of the Society of Fellows!

COMMUNICATING SCIENCE

Environmental Science Professor Anne Toomey’s recently published book, Science with Impact: How to Engage People, Change Practice, and Influence Policy, gains media attention in WCAI.