Landscape Management Internship in Prospect Park

Talulah Barni completing fieldwork in Prospect Park this past summer.

While going through some of my old assignments, I recently stumbled across a piece I had written for one of my environmental classes last year. I wrote about some of my potential career goals for the future and what my plan would be going forward with my environmental path. I explained that one of my goals after graduation was to intern for the NYC Parks department. Originally, I had wanted to work for the NYC Parks department because of its well-known status, and because the Parks department sounded like a solid starting point for any career I may have chosen in the environmental sector. I also wanted something close to home that felt familiar to me since I am originally from Manhattan. However, I didn’t think the dream would come to fruition because at the time, I had very vague career goals and was uncertain that a Parks internship would be the best fit for what I planned to do after graduation. For this reason, I soon forgot about the goals I outlined in that reflection piece as I made the decision to pursue a career in Library Science. At the beginning of Spring 2023, I was looking around for internships and saw an Ecological Restoration position through the NYC Parks department available for Summer 2023. Even though I had long ago forgotten about the goal of working at Parks, the opportunity excited me because I wanted to try a new experience within the environmental field and try hands-on learning outside of a classroom setting.

Looking back, I’m so glad everything came full circle, and I was able to have this wonderful summer experience. Working with the Prospect Park Alliance team was an amazing opportunity and everyone I met had a clear passion and love for the work that they do for the park every day. And even though I plan on making a pivot to pursue job opportunities that will not require me doing environmental monitoring, this experience helped me grow a lot personally and develop skills to be a valuable team member. I became more confident in my plant knowledge, which was an important personal goal that I had for myself. I also learned how to tolerate harsh outdoor weather conditions and push through difficult physical tasks I didn’t always want to do. In terms of professional progress, I learned how to work better on a team by asking questions and splitting up shared work. I also practiced communicating with an internship supervisor, which is a skill I will need in any other professional endeavor that I may pursue. Our work consisted of Ecological Assessment, Site Maintenance, Rapid Site Assessments, Data Entry, and other important park projects. I was grouped with a team of three other interns for the duration of the summer and our work supervisor led all our park activities.

When the internship first started, a lot of our work consisted of getting familiar with the flora of Prospect Park. Even though my previous coursework at Pace as an Environmental Studies major introduced me to basic concepts around plant identification (ID), data collection in a field setting, and native vs. invasive species, I had almost no previous knowledge about native plants in the area going into the summer. Getting better at plant ID was a personal goal that I had hoped to fulfill during the summer because I find it an impressive skill that I wanted to improve as a personal hobby. I also thought this skill would be valuable in any future jobs where I would need to have a deeper understanding of multiple kinds of plants (e.g. Working in an Herbarium or developing children’s library programs related to native plant identification). This internship did a great job of helping me not only learn the names of plants, but also getting a better idea of what kinds of plants should be planted in which weather and light conditions as well as how aggressive certain plants are.

It was imperative that by the end of this internship we could easily identify frequently occurring native and non-native species. This was done so that we could conduct trail maintenance in which we removed certain plants and left others to grow. Trail maintenance is an important activity for the park because the removal of invasive species (i.e., non-native species that cause environmental harm) allows native species to dominate where they wouldn’t normally be able to due to the invasive species out-competing them. My supervisor (Mr. Howard Goldstein, Senior Forest Ecologist for the Prospect Park Alliance) used our first week to get us familiar with the park so that we knew the names of various locations if we ever needed to meet up somewhere. Mr. Goldstein did a fantastic job teaching us plant identification and he was always willing to answer any questions we had. We also did site maintenance throughout the summer which consisted of invasive species removal in different parts of the park. We mainly worked on removing invasive vines and shrubs like Hedera helix (English Ivy), Ampelopsis brevipedunculata (Porcelain Berry), and Rubus phoenicolasius (Wineberry). While important and rewarding, trail maintenance is taxing work and can be physically demanding. I had to make sure that I had plenty of water during our outdoor sessions and I took multiple breaks to cool down. Several plants are painful due to their sharp thorns, so I had to be careful when handling them and make sure I had gloves. However, in addition to helping the park with getting rid of these ecologically damaging plants, doing invasive species removal allowed me to help people in my personal life by advising which plant species they should remove from their backyards and explaining why it matters.

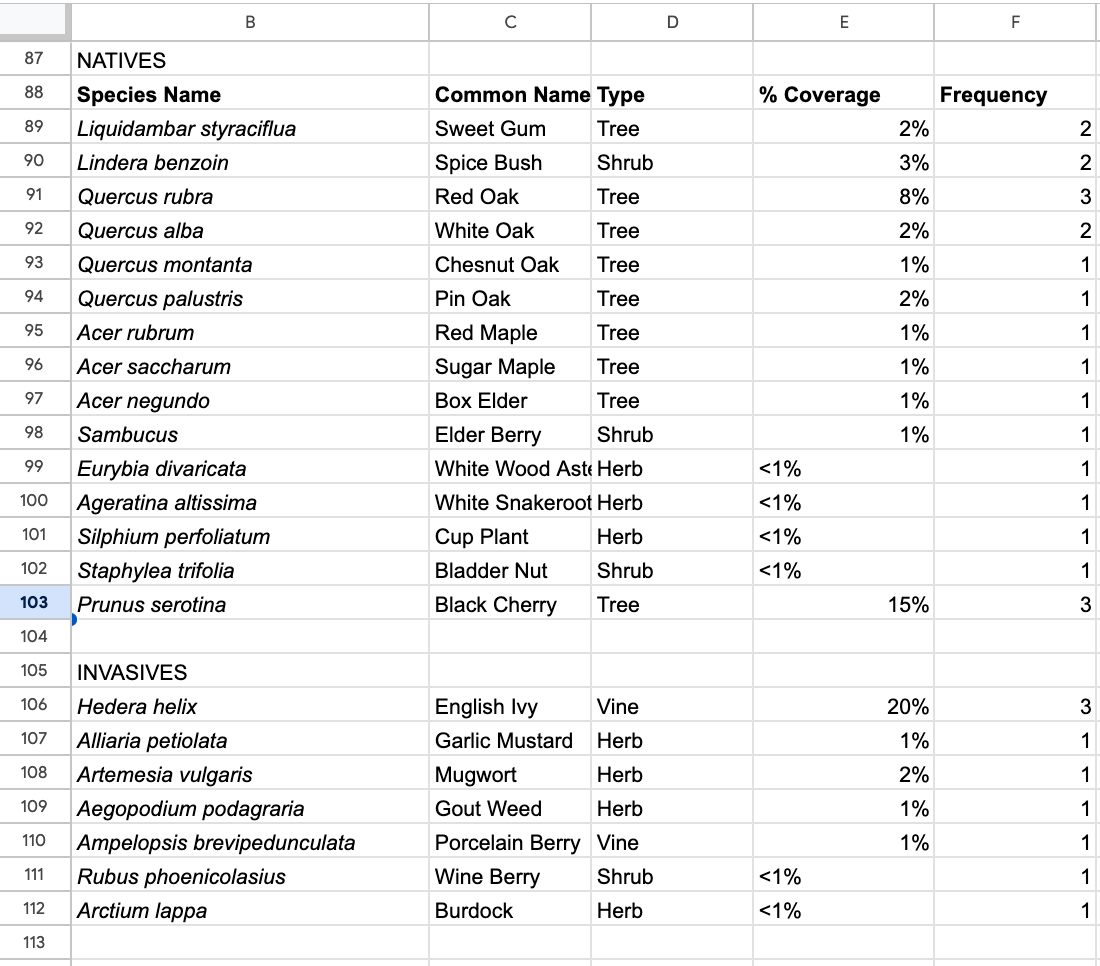

Figure 1: These are the data entry sheets we used this summer to input groundcover species data. We separated the native and invasive species and listed their species names and common names. We also included the plant types, percent coverage, and frequency of each species at each eco-assessment site.

The middle of the summer consisted of several ecological assessments (eco-assessments) and the introduction of the Rapid Site Assessments (RSAs). Our supervisor created the ecological assessments to have a broad quantitative method of determining site health. Because of the extremely detrimental effect invasive plant species can have on native species, site health was determined by the extent to which non-native species, specifically non-native species that are becoming highly invasive to an area, were crowding out natives. If a site was deemed unhealthy, this would be due to an overabundance of invasive species that can damage the ecosystem and reduce biodiversity. I didn’t have any previous knowledge of both the ecological and rapid site assessments prior to the summer, but both assessments acted as educational exercises for me to practice my plant identification as well as learn how to properly assess a site with quantitative ecological methods. The eco-assessments consisted of determining all plant species in an area by recording frequency and coverage values through observation of the site. The RSAs consisted of the same concepts with a more in-depth measurement of each tree within the site and standardized methods to ensure that sites being assessed were the same size. For the latter, each site was measured with open reel measuring tapes 10m in each cardinal direction. The RSAs are the standardized method used by all the NYC parks and the data from these assessments are sent to the NYC Parks Department to aid in making their management priorities and decisions for all NYC parks. For this reason, it is important that the sites be a consistent size to ensure that sites can be compared from year to year and across different parks. Most of our time during the middle of the summer consisted of the eco-assessments compared to the RSAs.

To carry out the eco-assessments, each site in the park was identified using a predetermined ID number that reflected its specific site name and area code. For example: “0103VW02”. When conducting the eco-assessments, we would observe the entire site and record all the plants (grasses, forbs, shrubs, and trees) in the area. If a plant couldn’t be identified by the interns or our supervisor, the app “Picture This” was used for the ID. Each plant that was identified would be recorded as either a native species or invasive species. Two separate recording sheets would be used for the natives vs. invasives. During our eco-assessments, we wanted to see as many native trees and plants in our sites as possible. Native plants naturally occur in their environments of origin and greatly benefit local wildlife by providing them with food and shelter. We wanted to see less invasive species in our sites since they can be very aggressive and crowd out native plants. Some examples of native plants and trees in Prospect Park include: Eurybia divaricata (White Wood Aster), Toxicodendron radicans (Poison Ivy), Tilia americana (American Basswood/Linden), and Liriodendron tulipifera (Tulip Tree). Some of the highly aggressive invasive plants and trees we encountered included: Artemesia vulgaris (Mugwort), Broussonetia papyrifera (Paper Mulberry), and Alliaria petiolata (Garlic Mustard).

After recording all the plants observed in a particular site, we would collaboratively decide on and record percent coverage and frequency of each species. Overall, several sites were deemed healthy, but I remember a few areas were considered “active restoration” sites and needed more trail maintenance to be done to clear out invasives. Percent coverage was defined as the percentage of the site that a plant species populated. Our range was from (<1% to 100%). For example, if half the ground cover of a site consisted of Parthenocissus quinquefolia (Virginia Creeper), we may say that the percent coverage of this vine would be 50%. Frequency referred to how often we saw a plant throughout a site. Our range was a 1-5 scale. My supervisor described it as imagining a site split up into a grid. If we are looking at a plant species, we would want to imagine how many squares of the grid this plant species would show up in. For example, if we spotted several Prunus serotina trees (Black Cherries) throughout a site, we may say that the frequency is 3 since the tree species is quite prevalent.

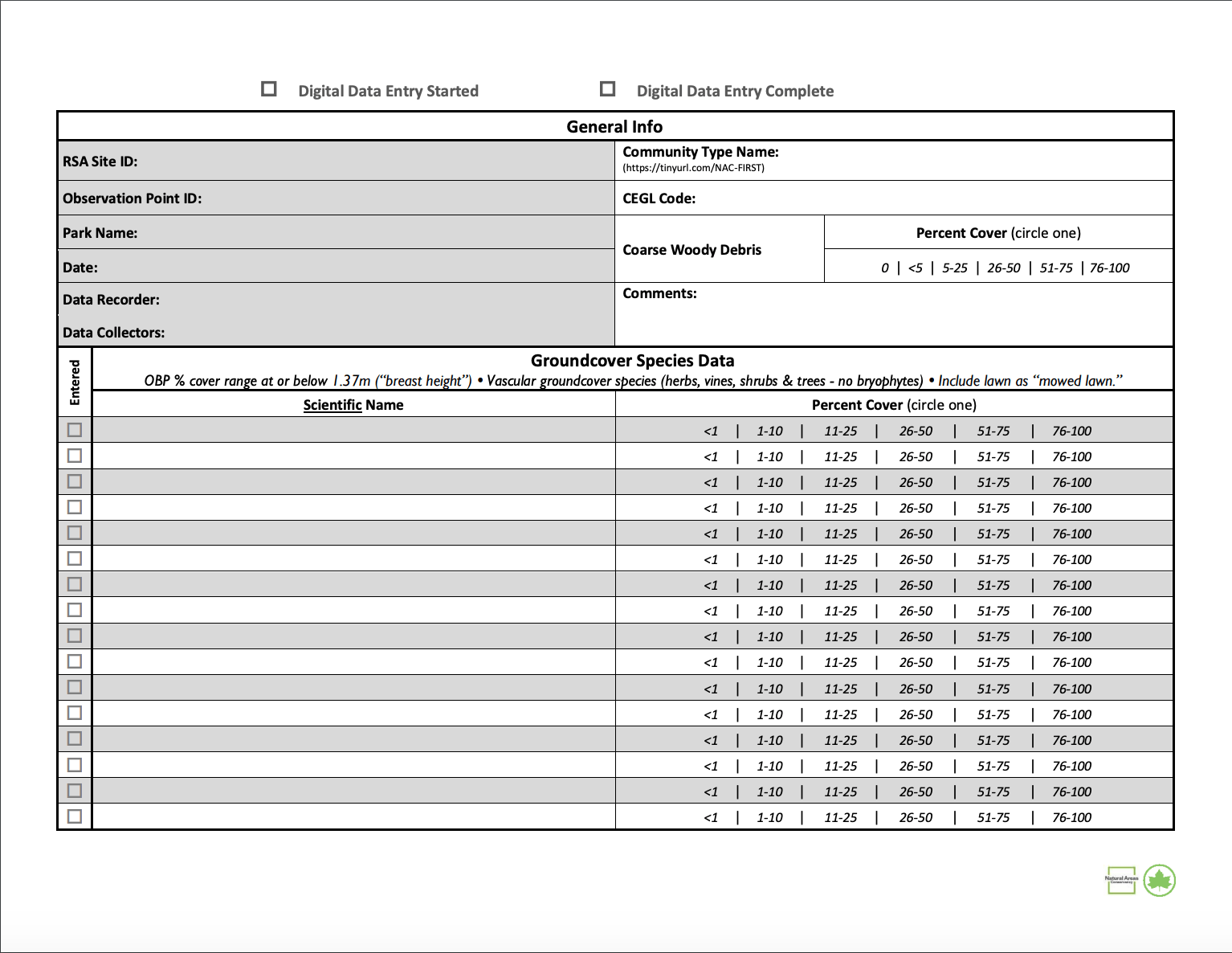

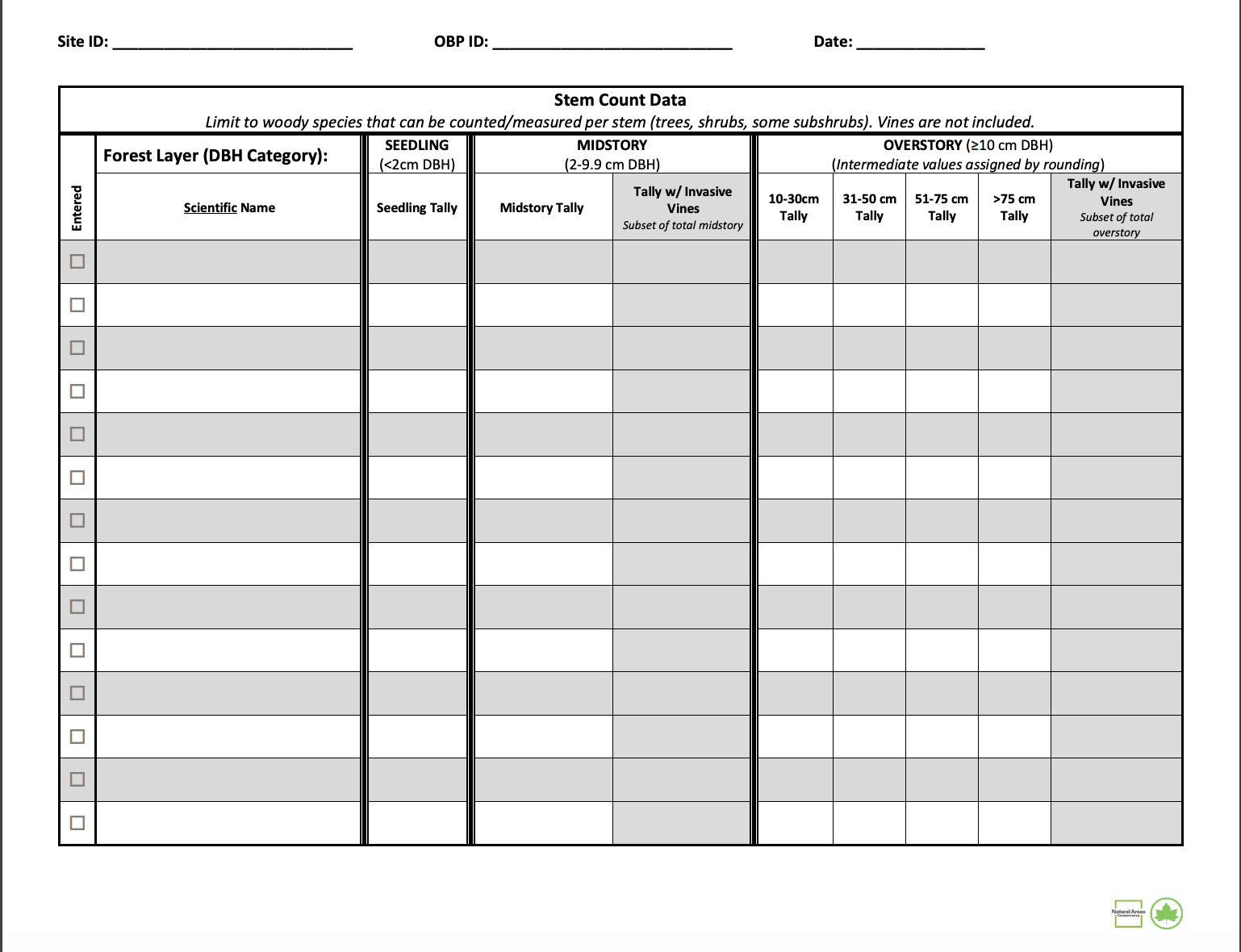

Figures 3 and 4: These are the official Rapid Site Assessment checklists where we would record our data from each RSA site. The first sheet covers general information and groundcover species data while the second sheet includes stem count data.

End of Summer

As the summer ended, we dove headfirst into the Rapid Site Assessments (RSAs), which were similar to the eco-assessments but different in a few key ways. The RSAs required us to record percent coverage of all plant species like the eco-assessments as well as recording all the plant species seen in an area to gauge native vs. invasive plant coverage, but the RSAs, unlike the eco-assessments, included tree measurements at each site. The RSAs were officially created by the Natural Areas Conservancy (NAC) in collaboration with the NYC Parks Department as part of the ongoing Forest Management Framework initiative. These RSAs are the standardized method for all NYC Parks to follow when conducting the assessments to further improve park restoration and management, while the eco-assessment data are collected at Prospect Park only to support its internal management decisions and practices. Healthy forests have a diverse range of tree sizes and ages. If a forest only has older trees and no new tree growth, this may be an indication that the forest is unhealthy. For this reason, keeping track of midstory (younger and/or smaller-sized) and overstory (older and/or large-sized) trees was important for the park to see if the trees were growing over time.

Materials:

– Two DBH tapes

– Six Open Reel measuring tapes

– Multicolored chalk

– Carabiner

– 2 metal wire stakes

– 10-20 Stake Flags

A special smartphone app was used to determine 4 random pinpoint locations within the park’s designated RSA sites. These RSA locations allow park staff to conduct forest health assessments at the exact same spots every year. This allows for a certain level of continuity and repetition to determine site health, biodiversity, and forest succession over time. In my undergraduate environmental classes at Pace University, I was introduced to similar data collection methods that included the same techniques as replication and standardization. I felt that this internship helped strengthen my confidence with these approaches and gain valuable experience applying them. Through the RSAs the Parks Department is better informed about the state of their wild greenspaces over time. Once an RSA is assessed, the department can begin to mitigate against potential problems and threats to biodiversity and plant health. At each of the four points, a metal stake was placed into the ground and secured with another metal stake. A carabiner was attached to the stake and all 6 open reel measuring tapes were clipped on. Once each tape was secure, four of the tapes were walked in each of the four cardinal directions. The other two tapes were walked in between two of the spaces between the original four tapes to make a total of 8 “pie slices.” Each slice was assessed, and the names of each plant species observed was recorded. It was imperative that we recorded the scientific names of each species instead of their common names to eliminate any ambiguity of which species was observed. Each plant species recorded would be given a percent coverage range like 10-22% that we believed it fell into. These ranges would be discussed among the group before deciding. We also made notes of any site details and important information. Once we had recorded all the tree species in the site on a separate sheet, we marked each one with a chalk mark so they would not be repeated. For each tree, we grouped them into the categories of seedling, midstory and overstory. Trees with vines were marked in their own category along with the main size categories. After all the trees had been marked and measured, we collected our materials and moved onto the next location point. Each point would be completed with an RSA until the entire site was finished.

Figure 3: Open reel measuring tapes used to divide up the sites into “pie slices” during the process of conducting the RSAs.

Going into the internship this summer, I wanted to gain work experience and learn what an environmental job is like from day to day. My expectations were both met and exceeded because I truly got to learn skills that I can use both personally and professionally. During my time at Pace University, many of my environmental classes had introduced some of the skills and topics that I used almost daily at the park (plant ID, invasive species, DBH measurements, the basics of study design and data collection). However, the internship provided much more in-depth learning and application of these skills and topics, which was interesting and rewarding. While I most likely won’t go into the environmental job market for personal reasons, I do have plans of pursuing a Master’s in library sciences. I know the skills that I learned this summer will be useful for any future internships I pursue in a library career, particularly in internships around environmental education and outreach, and I am interested in promoting environmental education at public libraries through engagement with youth programs.

Talulah Barni '24

Environmental Studies

Talulah Barni is a Pace University senior pursuing her BA in Environmental Studies. She had the opportunity to intern for the Prospect Park Alliance under the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation during the summer of 2023. She enjoys taking long walks, spending time in nature, and plans to promote environmental literacy and education to young people in her future career.

Recent Posts

Launching the Native Plant Propagation Project

Learn more about the Native Plant Propagation Project, an educational program to showcase the diversity of local native plants and their benefits to the biodiversity of a region.

New Nesting Boxes in the Conservation Center

If you’ve walked the Conservation Center grounds on the Westchester Campus this spring, you may have noticed wooden nesting boxes placed in various locations. These boxes are being monitored for breeding bird activity, and the recorded data is actively being submitted to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology NestWatch program.